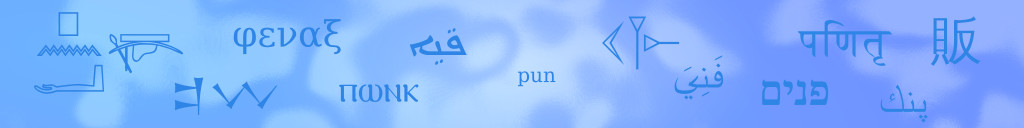

Introduction to Semitic

I’ve started to write an introduction to some aspects of the Semitic languages here, especially to some special script and grammar forms, which are important to identify puns. So far it’s mostly about my understanding of Hebrew; I’ll add other languages later as I learn more about them.

Consonantal script

All Semitic languages are written in consonantal abjad scripts, i.e. all letters are consonants. The languages all have vowels, of course, but they were not written down. This is similar to Ancient Egyptian.

Most Semitic grammars also have the feature that in any text, the root form of each word is relatively clearly visible, because no grammar forms take letters away, and very few letters are added, typically only as prefixes or suffixes.

Still, because the script omitted all vowels, because spelling had not yet been standardized, and because of overlapping spellings & meanings, many words in ancient texts were ambiguous. This probably gave rise to the use of puns for encryption.

Transliteration of Semitic letters

I don’t speak the Semitic languages, and most other truth-seekers don’t either. To make the punnery understandable to us, I’ll transliterate & transcribe the Semitic letters into Latin letters. Transliteration is a 1:1 mapping. Transcription is not a strict mapping, but an attempt to write down the pronunciation of a word in the way an English speaker would write it, with vowels.

I often give a word in all 3 forms, one after the other.

In most places, I try to give the spelling in original glyphs, plus a 1:1 transliteration with Latin letters, and sometimes a transcription with vowels. I think the 1:1 transliteration is the most important to understand the puns, as they mostly seem to ignore the vowels. I also usually omit the Hebrew “vowel dots”, which didn’t exist in the ancient scripts anyway. (Transliteration is also useful for comparison of languages with different glyphs, such as Hebrew & Ancient Egyptian).

- Original script: אלף

- Transliteration: ˀlp

- Transcription: aleph

- Translation: “cattle”

- All together: אלף ˀlp aleph “cattle”

I use the following Latin letters to transliterate Hebrew letters 1:1.

My transliteration mostly follows the standard, except for ˀAleph and ˁAyin, which I denote by ˀ and ˁ (as opposed to the barely visible standard signs ʾ and ʿ).

| Letter name | Hebrew | My transliteration | Numeric value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ˀAleph | א | ˀ | 1 |

| Bet | ב | b | 2 |

| Gimel | ג | g | 3 |

| Dalet | ד | d | 4 |

| He | ה | h | 5 |

| Waw | ו | w | 6 |

| Zayin | ז | z | 7 |

| Ḥet | ח | ḥ | 8 |

| Ṭet | ט | ṭ | 9 |

| Yod | י | y | 10 |

| Kaph | כ | k | 20 |

| Lamed | ל | l | 30 |

| Mem | מ | m | 40 |

| Nun | נ | n | 50 |

| Samekh | ס | s | 60 |

| ˁAyin | ע | ˁ | 70 |

| Pay | פ | p | 80 |

| Ṣade | צ | ṣ | 90 |

| Qoph | ק | q | 100 |

| Rosh | ר | r | 200 |

| Šin | ש | š | 300 |

| Tav | ת | t | 400 |

Interchangeability of Hebrew letters

Most encryption puns seem to be based on near-homonymity & near-homography, i.e. words that were spoken & spelled very similar, though not identical. So to find puns in ancient texts, it is very, very important to develop a feeling which letters felt “similar” for the speakers of a certain language.

For living languages, we can judge from our pronunciation, or even from English equivalents of the phonemes. For extinct languages & ancient versions, good clues for “similarity” can be found in spelling variations: When one word or related words occur with spelling variations, it means that at least some speakers must have considered the varied letters to be exchangeable or interchangeable.

Of course, “interchangeable” does not mean every speaker & writer of the language would exchange these letters at random. Rather, there was typically a standard orthography & pronunciation. It simply varied somewhat between dialects, between regions, between epochs, between related words of the same word root, and sometimes by scribal error.

In most cases, understanding this “interchangeability” is straightforward: e.g. letters that stand for S-ish phonemes are interchangeable in all languages, because their phonemes are similar or overlapping. Still, I made a list here of exchangeable letters, mostly for the not-so-straightforward cases.

(A very good source for interchangeability is the Ernest Klein dictionary.)

Dalet ≈ Ṭet ≈ Ṣade ≈ Tav

All T-ish sounds are interchangeable to some degree. Arabic Ḍad also belongs into this group. Ṣade is a T/S hybrid, so it also belongs into this group. A Ṣade/Ṭet switch occurs regularly between Hebrew & Aramaic, though not with all words.

Examples:

- פרד prd = divide, break apart; פרט prṭ = divide, break; פרת prt = divide, break off; פרץ prṣ = break open

- חתף ḥtp = seize; חטף ḥṭp = seize

- יעט yˁṭ = counsel, plan; יעץ yˁṣ = counsel, plan

- נצר nṣr = guard (Hebrew); נטר nṭr = guard (Aramaic)

Gimel ≈ Qoph ≈ Kaph ≈ Ḥet

All K-ish sounds are interchangeable to some degree. (Arabic Ḫa also belongs into this group.)

Examples:

- כנז knz = hiding; גנז gnz = hiding

- כשט kšṭ = shoot arrow; קשט qšṭ = shoot arrow

- גבל gbl = bound, border; כבל kbl = bind, chain; חבל ḥbl = bind, rope

- גמר gmr = ripen; כמר kmr = ripening fruit; חמר ḥmr = wine

- רכל rkl = go about, slander; רגל rgl = move, run, slander

- סכר skr = shut up, stop up; סגר sgr = shut, close

- קרץ qrṣ = cut, incision; חרץ ḥrṣ = cut, incision

- גומץ gwmṣ = pit; קומצא qwmṣˀ = pit

- גמר gmr = heat, burn with coal; כמר kmr = heat, burn, warm; חמר ḥmr = burn, glow, parch

Zayin ≈ Samekh ≈ Ṣade ≈ Šin ≈ Tav

All S-ish sounds are interchangeable to some degree. In most Semitic dialects, Tav is pronounced soft and S-ish like English th, so it belongs into this group. Arabic Ẓa also belongs into this group. Ṣade is a T/S hybrid, so it also belongs into this group.

A Šin/Tav switch occurs regularly between Hebrew & Aramaic, though not with all words.

Examples:

- יסף ysp = adding (Hebrew); יזף yzp = adding (Aramaic)

- שני šny = repeat (Hebrew); תני tny = repeat (Aramaic)

- צדק ṣdq = righteous (Hebrew); זדק zdq = righteous (Aramaic)

- צחק ṣḥq = laugh; שחק šḥq = laugh

He ≈ Ḥet

The letters He & Ḥet are designed to look very similar in all Semitic scripts. Depending on dialect & region, Ḥet could be scratchy and K-ish, or almost silent and H-ish. (Arabic Ḫa also belongs into this group.)

Examples:

- הברא hbrˀ = darkness; חבר ḥbr = dark

- פתה pth = wide, open; פתח ptḥ = widen, open

- גלה glh = uncover, reveal (Hebrew); גלח glḥ = stretch out, reveal (Aramaic)

ˀAleph ≈ Yod ≈ He

The vowel-like letters Aleph, Yod, He are very often exchangeable, especially at the beginning or end of words. As a suffix, the letter He is more common in Hebrew, Yod and Aleph are more common in Aramaic. All endings occur in all dialects though.

Examples:

- שנא šnˀ = change; שנה šnh = change; שני šny = change

- ראש rˀš = head; רישא ryšˀ = head; ריש ryš = head

Bet ≈ Pay

The B-ish letters are interchangeable.

Examples:

- בזר bzr = scatter; פזר pzr = scatter

- בלש blš = dig, investigate; פלש plš = dig, inquire

- בעבע bˁbˁ = bubble; פעפע pˁpˁ = bubble

Bet ≈ Waw

Both Bet & Waw can denote a V-like phoneme. They are thus interchangeable.

- בּ = B written as Bet

- ב = V written as Bet

- ו = V written as Waw

Examples:

- לוה lwh = join; לבב lbb = join

- לולי lwly = shout; לבלי lbly = shout

- שבח šbḥ = spread, germinate; שווח šwwḥ = spread, germinate

- כווי kwwy = burned, scorched; כבבא kbbˀ = burn to coal; כבב kbb = roasted meat, kabab

- הואי hwˀy = vanity; הבאי hbˀy = vanity

Dalet ≈ Zayin

This Zayin / Dalet switch occurs regularly between Hebrew & Aramaic, though not with all words.

Examples:

- בזר bzr = scatter (Hebrew); בדר bdr = scatter (Aramaic)

- כזב kzb = lying (Hebrew); כדב kdb = lying (Aramaic)

- עזר ˁzr = help (Hebrew); עדר ˁdr = help (Aramaic)

ˀAleph ≈ ˁAyin

Both ˀAleph & ˁAyin are glottal stops. ˀAleph is the open-mouthed glottal stop, ˁAyin is more throaty. Usually, a certain word occurs only with one or the other spelling, but both letters and their phonemes are similar, and thus interchangeable. Mostly, dictionaries don’t list these alternative spellings though, or only as minor redirection entries to the standard spelling.

Examples:

- אין ˀyn = look; עין ˁyn = look

- כאן kˀn = now; כען kˁn = now

- כאר kˀr = ugly; כער kˁr = ugly

- ארעי ˀrˁy = chance; עראי ˁrˀy = chance

- אלם ˀlm = connect, tied up; עלם ˁlm = join, tie up

- עץ ˁṣ = wood (Hebrew); אע ˀˁ = wood (Aramaic)

- גלא glˀ = reveal, uncover; גלע glˁ = disclose

Lamed ≈ Rosh

Lamed & Rosh are somewhat similar, and there is the rare occasion of words with the same meaning where these letters are exchanged.

Examples:

- בזר bzr = scatter; בזל bzl = scatter

- הבל hbl = vapor; הברא hbrˀ = mist

- חלץ ḥlṣ = loin (Hebrew); חרץ ḥrṣ = loin (Aramaic)

Gimel ≈ ˁAyin

ˁAyin is a very throaty glottal stop, close to pronouncing a G-like sound. Gazah & Gomorrah are both transcribed with G, but in Hebrew they’re written with ˁAyin, not Gimel. Arabic differentiates between ˁAyin & Ġayin, both letters designed to look very similar. In Hebrew & Aramaic this distinction cannot be written down due to fewer letters, but it was perhaps pronounced in some dialects.

Examples:

- עוף ˁwp = wing, bird, fly (Hebrew); גף gp = wing (Aramaic)

- בעבועי bˁbwˁy = bubble; בגבוגי bgbwgy = bubble

Ḥet ≈ ˁAyin

ˁAyin is a very throaty glottal stop. Ḥet is a scratchy sound also made with the throat, just not as far down. The switch occurs sometimes between Hebrew and Aramaic.

Examples:

- חב ḥb = bosom; עובא ˁwbˀ = bosom

- חוף ḥwp = bend over; עוף ˁwp = bent

- גלח glḥ = reveal, expose; גלע glˁ = disclose

Ṣade ≈ ˁAyin ≈ Qoph

I cannot explain this, but it is undeniable: The 2 letters Ṣade & ˁAyin are designed to look very similar, and there are synonyms where one is simply swapped for the other. As usual, this means these spelling variants are actually the same word, and different speakers used both letters to write the same phoneme. The letter Qoph also sometimes occurs in the place of Ṣade & ˁAyin. This phoneme similarity must go back to archaic dialects. It has been mostly lost in modern pronunciation, so a modern speaker wouldn’t see much similarity in the phonemes today.

Examples:

- ארץ ˀrṣ = earth; ארע ˀrˁ = earth; ארקא ˀrqˀ = earth

- רצץ rṣṣ = break, crush; רעע rˁˁ = break, crush

- צאן ṣˀn = small cattle; עאן ˁˀn = small cattle

- נפץ npṣ = shake, shatter; נפע npˁ = shake, shatter

- עץ ˁṣ = wood (Hebrew); עק ˁq = wood (Aramaic); אע ˀˁ = wood (Aramaic)

ˀAleph, Yod, He, Waw, ˁAyin omittable

All vowel-like letters are generally omittable when forming words within a word root. Those vowel-like letters would be ˀAleph, Yod, He, Waw, ˁAyin. In my experience, ˁAyin is the least ommittable: Many words can only be distinguished by ˀAleph vs. ˁAyin spelling.

In theory, this is only true when they have been inserted into a word for vowelization, and are not part of the word root. However, very often you find that the 3-letter word root given by a dictionary is not the ultimate word root. Rather, you encounter related forms where the vowel-type letter is not present. So I’d call those roots 2-letter word roots, with vowelized forms. The 3-letter orthodoxy of the dictionaries seems misleading.

To find puns, we can therefore omit or add all of these vowel-type letters, and see if we find similar words with the changed spelling.

When analyzing actual language, we can likewise look for words where one of these vowel-like letters has been omitted or added, and will often see that they still belong to the same word root.

Examples:

- יעט yˁṭ = cover; עטה ˁṭh = cover

- יעץ yˁṣ = counsel; עצה ˁṣh = counsel

- יזף yzp = borrow; זפה zph = loan

- ארבע ˀrbˁ = four; רבע rbˁ = fourth, square

- לעג lˁg = mock; לגלג lglg = mock

- בד bd = lie; בדא bdˀ = invent, liar; בדיה bdyh = lie; בדיאה bdyˀh = falsehood; בדו bdw = mistake

- גבה gbh = high; גבע gbˁ = high

- גלא glˀ = reveal, uncover; גלי gly = reveal, uncover; גלה glh = disclose; גלע glˁ = disclose

Rearranged consonants by metathesis

Language has formed natural anagrams whenever dialects changed the order of consonants. Since the dialect speakers would consider these metathesized words to be interchangeable, anagrams would also count as being similar to each other.

- עמץ ˁmṣ = close eyes; עצם ˁṣm = close eyes

- כבש kbš = lamb; כשב kšb = lamb

- כבש kbš = subdue; כשב kšb = subdue

- ארכבה ˀrkbh = knee; ברך brk = knee

The 5 Saadia Gaon letter groups

People who study Biblical wordplay sometimes cite the Saadia Gaon system of 5 groups. The groups are formed according to where in the mouth the sound is formed. In theory, this could be the key to decrypt all those spooky puns, at least for Hebrew & Aramaic.

In practice, some letter swaps from real-life spelling variants are not possible within this system, such as Kaph ≈ Ḥet, ˀAleph ≈ Yod, Gimel ≈ ˁAyin, plus all the Hebrew / Aramaic swaps. The Gimel ≈ ˁAyin swap even occurs with an obvious Biblical pun: gmr “burn-to-coal” puns with the burned-to-coal city ˁmrh “Gomorrah”! So, there are definitely puns outside this system, and it doesn’t help us with other languages either.

I’ll still list the 5 groups here, because this officially sanctioned system may yet explain some of the “fuzzier” puns.

| Group | Letters | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| throat | ˀAleph א, Ḥet ח, He ה, ˁAyin ע | |

| palate | Gimel ג, Yod י, Kaph כ, Qoph ק | Yod seems a bit odd here. |

| tongue | Zayin ז, Šin ש, Samekh ס, Rosh ר, Ṣade צ | Rosh seems very odd here. |

| teeth | Dalet ד, Ṭet ט, Lamed ל, Nun נ, Tav ת | Lamed & Nun seem very odd here. |

| lips | Bet ב, Waw ו, Mem מ, Pay פ | Mem seems a bit odd here. |

Prefixes in Hebrew

I list Hebrew prefixes here, but they are often the same for Aramaic, and even Arabic.

Prefixes are a common tool to create puns: You can often add them to any word without changing the meaning, and the new word then becomes similar to another word that the spooks want to encode.

Prefixes can also be combined.

This list is non-exhaustive. I only list those prefixes that I feel are important for the puns.

Nun-prefix

The Nun-prefix denotes the Niph‘al passive / reflexive form.

Examples:

- זר zr = stranger; זור zwr = turn aside; נזר nzr = separate oneself, become a Nazirite

- סתר str = hiding; נסתר nstr = self-hidden person

Mem-prefix

The Mem-prefix means “from” or “of”. It is a typical nominalization prefix where it has no meaning. The Mem can thus be prefixed to any word to create a pun similarity. (This prefix is also found in Egyptian.)

Bet-prefix

The Mem-prefix means “with” or “in”. It is also a nominalization prefix, occurring less often. It does not change the meaning, and can in theory be prefixed to any word.

Šin-prefix / Tav-prefix

The Šin-prefix / Tav-prefix means “that” or “which”. Šin is the Hebrew form, Tav the Aramaic one. It is also a nominalization prefix (“that which is X”), though in the dictionaries it is apparently only included when the Aramaic Tav-form was loaned into Hebrew. It does not change the meaning, and can in theory be prefixed to any word.

Tav is also sometimes prefixed to verbs, though the meaning varies here, and I haven’t found an exhaustive overview. Mostly, it seems to denote the imperative as in “you shall do XY”. Again, it can in theory be prefixed to any verb, so often you find a verb root by stripping it.

Lastly, Šin is also prefixed to verbs to form new verbs, as a form of causative. The only explanation I found is in Klein’s Dictionary, where he references it frequently. But it’s undeniable that many causative words are formed this way. Klein calls the form Shiph‘el & Shaph‘el.

Genesius calls these conjugations with Šin & Tav prefixes Taph‘el & Shaph‘el. However, he gives verb examples only for Tav, even though Klein shows they also exist for Šin.

Dalet-prefix

The Dalet-prefix is a somewhat rare nominalization prefix, occurring more often in Aramaic. It can mean “of”, “which”, “from”.

He-prefix

The He-prefix can mean “the”, which is almost meaningless. But it also denotes the causative Hiphi‘el & Hopha‘el grammar forms. A causative can reverse the meaning of a word, and is thus a very significant change. For example, the creditor / debtee is usually a rich & powerful person, while the creditee / debtor is usually poor & powerless. That’s why spooks often don’t call themselves Levi, but HaLevi. They want to be the ones causing things.

As usual in ancient languages, this explicit grammar is not needed, a causative is more often implied / inferred by the context.

Kaph-prefix

The Kaph-prefix means “like” or “as”. It has a very specific meaning, and is not typically used for nominalization.

Lamed-prefix

The Lamed-prefix means “to”. It has a very specific meaning, and is not typically used for nominalization. (This prefix is found in Egyptian as an R-prefix, since Egyptian script didn’t have an L.)

Suffixes in Hebrew

I list Hebrew suffixes here, but they are often the same for Aramaic, and even Arabic.

Suffixes are a less useful tool to create puns, because there are very few of them. It still important to identify them though, because you often have to strip them away to get the root form of a given word.

This list is non-exhaustive. I only list those prefixes that I feel are important for the puns.

Nun-suffix

The Nun-suffix has puzzled me a lot, because there are few good explanations available.

In Hebrew, the Nun-suffix is mostly an agent noun suffix, i.e. it denotes the person who does something. In English, this would be the -er suffix: A baker is a person who bakes.

The Nun-suffix can also denote abstract nouns, though that seems to be a modern development.

In Aramaic though, the Nun-suffix occurs with general verb forms, so it can be attached to any verb. As for nouns, the Aramaic masculine plural -yn also ends with Nun.

So as a rule, when we encounter the Nun-suffix in a Biblical name, it probably just means “person who is X”. A good example is Samson. When we encounter the Nun-suffix in Talmudic literature, it is very often just a verb or noun ending, and to find the root form we need to strip it.

Suffixes -ym & -wt

The suffix -ym denotes the masculine plural. The suffix -wt denotes the feminine plural. The suffixes -wt / -t also denote (mostly abstract) nouns. Both can be stripped to get the word root.

When Biblical names have an obvious plural ending, such as Elohim or Mitsraim, closer inspection is warranted: They’re likely puns that encode a group of people.

(The female plural suffix -wt is found in Egyptian as a T-suffix for the female singular.)

Duplication suffix

For many words, either the last non-vowel letter can be repeated in some forms, or the last 2 letters can be repeated. For some 2-letter words, this is a repetition of the entire word. Very rarely, only the first letter is repeated. None of these duplications change the basic meaning.

Examples:

- לעג lˁg = mock; לגלג lglg = mock

- גלשׁ glš = bald; גלשׁלשׁה glšlšh = baldness

- בלע blˁ = confusion; בלל bll = confuse; בלבל blbl = confuse

- גלא glˀ = reveal, uncover; גלל gll = unfolded, visible; גלג glg = reveal, uncover; גלגל glgl = revealed

Infixes in Hebrew

I know only of one infix, the Hitpa‘el Tav-infix, but it’s very important, and occurs in Hebrew & Aramaic. (Yod & Waw vowelization is sometimes called infixing, but I find that misleading, as it’s not actually forming any new words or grammar forms.)

Tav-infix

With the Hitpa‘el reflexive verb form for “doing things to oneself”, the letter Tav is sometimes infixed, i.e. inserted into a word after the 1st letter.

The general rule for Hitpa‘el is that the letters He & Tav are prefixed to the word root (the “Hit” in Hitpa‘el). However, if the original first letter is Šin or Samekh, then the letter Tav is instead infixed into the word, after the original first letter. And when the first letter of the original root is Ṣade or Zayin, then the infixed letter becomes a Ṭet or Dalet. (This again confirms the interchangeability of Dalet & Ṭet & Tav.) Similar rules exist for Arabic.

Generally, if the first letter is an S-ish letter, then an H is prefixed and a T-ish letter is infixed. The precise form depends on the S-ish letter (the dots stand for the other letters of the root form):

- s… → hst…

- š… → hšt…

- ṣ… → hṣṭ…

- z… → hzd…

This is the only Semitic infix grammar I’m aware of. It is important though, because it changes the consonantal “footprint” or “signature” of a word significantly: A new letter (Tav or Ṭet or Dalet) appears in the middle of a word. This can be used for puns. I think this grammar form is the explanation for names like Hadassah and Stein, because they are similar to a Tav-infixed grammar forms.

As usual in ancient languages, this explicit grammar form is not needed. A reflexive is more often implied / inferred by the context. Even in English, when you say “disguise”, people will usually infer that someone “disguised himself”.

Examples:

- שנה šnh = to disguise; השתנה hštnh = to disguise oneself, become different

- סמם smm = to poison; הסתמם hstmm = to poison oneself

- צער ṣˁr = annoy, trouble; הצטער hṣṭˁr = feel pain, trouble one’s self

- זוג zwg = join, couple; הזדווג hzdwwg = joined, wedded