Introduction to punnery

Puns have been used for cheap encryption by our secret spooky rulers for millennia. It’s so simple you wouldn’t believe it works: They just substitute words for others that are written or spoken somewhat similar. But since they only encrypt against their own unsuspecting & powerless subjects, that is often sufficient.

What are encryption puns?

Puns were known throughout the ancient world. But here’s a secret kept until today : Puns were also used by the elites to encrypt texts against their own subjects. I suspect that many ancient texts which seem hard to understand really have a punny double-meaning!

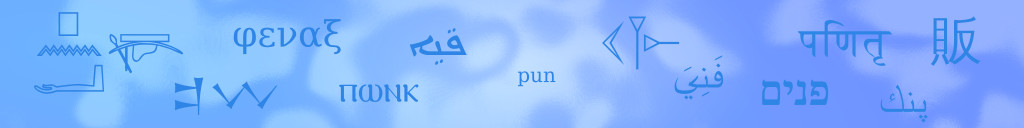

I use the word “pun” for this encryption system, because it’s short & catchy, and reminds us of the Phoenicians. However, these “encryption puns” don’t always work exactly like English puns. A better description would be “substitution by words that are roughly similar when written only in consonants”. But until we’ve come up with a better way for saying for that, I’ll just call them “puns”.

I’ll try to explain the pun-encryption system here using admitted examples from the Hebrew Bible.

- Similar when written: The English pun, where a guy yells “duck!!!” and it’s just a duck, uses perfect homonyms, written & spoken exactly alike. Spook encryption, however, is mostly about how words are written, and not how they’re spoken. After all, they wanted to defraud their less literate subjects.

- Consonants only: Spook encryption seems to stem from the ancient abjad scripts where you only write down the consonants. The spook encryption puns thus ignore all vowels completely, even those few that are written down. You could call this type consonantal homographs. An admitted example is ˀdm adam “man” being made from dmh damah “earth” (Genesis 2:7). The letters ˀAleph & He don’t count, because they’re vowels here. Only the D & M count.

- Word root only: Prefixes & suffixes can also be ignored if it suits the pun, even if they are consonants. An admitted example is Moses’ nḥš-nḥšt “serpent of bronze” (Numbers 21:9), because the -t in “bronze” is simply a suffix to form nouns. Another admitted example is ˀdm adam “man” being formed in God’s dmwt demuth “likeness” (Genesis 1:26), because -wt is also a suffix to form nouns. I suppose you could call it consonantal word root homographs, because they reduce a word to its root.

So far, so easy. But sadly, it doesn’t stop here. It gets “fuzzy”.

- Only roughly similar: Many puns go a step further and also substitute words for others where even the root form is written only roughly alike. You could call them consonantal word root near-homophones, but I usually go with “fuzzy puns”.

- Letter duplication: Such “fuzzy puns” include cases where consonants are doubled. One admitted example is the people being bll “confused” in bbl “Babylon” (see Tower of Babel below).

- Near-homophone letter swap: Other “fuzzy puns” have consonants swapped for different ones with a roughly similar pronunciation, like S and Z, or T and D. One admitted example is the Egyptian ˁyr h-ḥrs “city of the sun” becoming a ˁyr h-hrs “city of destruction” (Isaiah 19:18). The letter Ḥet has been swapped here for the letter He, which is near-homophonous.

- Based on spelling variants: Which letters count as being “similar”? By trial-and-error, I went with attested spelling variants. Classical Hebrew scholars also cite the Saadia Gaon system of 5 groups, which is mostly identical but also includes some very “fuzzy” choices.

- Anagrams: Rarely but regularly, even anagrams seem to be used: An admitted example is nḥ mṣˀ ḥn “Noah found grace” (Genesis 6:8).

Generally speaking, all these patterns seem to follow the ways how natural language forms words out of consonantal word roots: Arbitrary vowels and grammar suffixes can be added, but consonants are only ever swapped for similar ones. Even anagrams sometimes occur in natural language as a metathesis or transposition, and omissions as apheresis & elision. A Foucault quote sums it up nicely:

All the vowels may replace one another in the history of a root, for the vowels are the voice itself, which knows no discontinuity or rupture; the consonants, on the other hand, are modified according to certain privileged channels: gutturals, linguals, palatals, dentals, labials, and nasals all make up families of homophonous consonants within which changes of pronunciation are made for preference, though without any obligation.

I’ll now discuss examples of admitted puns in more detail.

The Tower of Babel

The Tower of Babel is one of the most famous admitted puns, because the pun is even alluded to in the Biblical text itself, so it’s hard to deny. In that story, God and his peers “confuse” the language of the people, to prevent them from building a city & tower to the sky. The authors then explicitly state that the city was named “Babel” because of the “confusion”, and both words are clearly similar.

In the Hebrew text you’ll see what they mean: The word בבל bbl babel for the city “Babel” is written & pronounced similar to בלל bll balal for “confusion”. The bbl / bll homography isn’t perfect, but it’s absolutely clear from the verse that this is an intended pun.

Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.

hbh nrdh wnblh šm šptm ˀšr lˀ yšmˁw ˀyš špt rˁhw

הבה נרדה ונבלה שם שפתם אשר לא ישמעו איש שפת רעהו

Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the LORD did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the LORD scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

ˁl kn qrˀ šmh bbl ky šm bll yhwh špt kl hˀrṣ wmšm hpyṣm yhwh ˁl pny kl hˀrṣ

על כן קרא שמה בבל כי שם בלל יהוה שפת כל הארץ ומשם הפיצם יהוה על פני כל הארץ

Now I don’t want to offend religious people, but it should also be clear that this story has nothing to do with historical Babylon: No detail whatsoever about the actual Babylon is mentioned: no date, no king’s name, nothing. It’s just the name Babel attached to a “city & tower”. It’s often explained as a Ziggurat. But while those are impressive, they’re hardly reaching to the sky as in the story, and they’re not unique to Babylon either. This means it’s really just a pun!

The pun itself is even admitted. It’s just not admitted that it’s only a pun. Wikipedia wastes 30 chapters to “discuss” the historicity of the story, and admits the pun only in one of them:

Genesis 11:9 attributes the Hebrew version of the name, Babel, to the verb balal, which means to confuse or confound in Hebrew. The first century Roman-Jewish author Flavius Josephus similarly explained that the name was derived from the Hebrew word Babel (βαβὲλ), meaning “confusion”.

The question is why even this admitted pun is downplayed so much. The literal story is about deities preventing humans from being overambitious. You could debate that idea, but it’s hardly controversial enough to censor it. But knowing about other spooky puns, many found in the Bible, we can see that the hidden meaning is usually about rulers deceiving their subjects. The cryptocrats have pun-encoded teachings about cryptocracy! And that topic certainly fits the Tower of Babel: Without a religious context, it is a story where powerful entities “confuse” powerless people, to prevent them from ever attaining power.

More puns are likely hidden beneath, such as špt & dbr for a common “language” & “speech” punning with špṭ & dbr for a common “judgement” & “behavior”. The ˁyr-w-mgdl “city and tower” may mean ˀwr-m-gdl “understanding the nobility”. This means that the story beneath could really be about the spooky rulers confusing the common people, to prevent a common understanding of the nobility!!! You can read my full interlinear text analysis here.

Regardless of those other puns though, we already understand the following:

- In famous stories, central names are often chosen for homonymity with central topics. They’re puns.

- The pun-encrypted topic is often one of hiding, deceiving, confusing or masking.

For another more or less admitted Bible pun, see Esther, which is also a pun with “hiding” & “veiling”.

Horn & Ivory

To give an admitted example from another language, we can study the Greek phrase “horn & ivory” in Homer’s Odyssey.

The “gates of horn & ivory” are an officially admitted pun of κερας keras for “horn” with κραινω krainu for “fulfillment”, and of ελεφας elephas for “ivory” with ελεφαιρομαι elephairomai for “deception”.

It seems that the implicit rules for punniness are similar to Hebrew: Only the consonantal word stem counts, vowels and grammar suffixes are ignored.

Stranger, dreams verily are baffling and unclear of meaning, and in no wise do they find fulfillment in all things for men. For two are the gates of shadowy dreams, and one is fashioned of horn and one of ivory. Those dreams that pass through the gate of sawn ivory deceive men, bringing words that find no fulfillment. But those that come forth through the gate of polished horn bring true issues to pass, when any mortal sees them.

xein, ē toi men oneiroi amēchanoi akritomuthoi gignont, oude ti panta teleietai anthrōpoisi. doiai gar te pulai amenēnōn eisin oneirōn: ai men gar keraessi teteuchatai, ai d elephanti: tōn oi men k elthōsi dia pristou elephantos, oi r elephairontai, epe akraanta pherontes: oi de dia xestōn keraōn elthōsi thuraze, oi r etuma krainousi, brotōn ote ken tis idētai.

ξεῖν᾽, ἦ τοι μὲν ὄνειροι ἀμήχανοι ἀκριτόμυθοι γίγνοντ᾽, οὐδέ τι πάντα τελείεται ἀνθρώποισι. δοιαὶ γάρ τε πύλαι ἀμενηνῶν εἰσὶν ὀνείρων: αἱ μὲν γὰρ κεράεσσι τετεύχαται, αἱ δ᾽ ἐλέφαντι: τῶν οἳ μέν κ᾽ ἔλθωσι διὰ πριστοῦ ἐλέφαντος, οἵ ῥ᾽ ἐλεφαίρονται, ἔπε᾽ ἀκράαντα φέροντες: οἱ δὲ διὰ ξεστῶν κεράων ἔλθωσι θύραζε, οἵ ῥ᾽ ἔτυμα κραίνουσι, βροτῶν ὅτε κέν τις ἴδηται.

The phrase originated in the Greek language, in which the word for “horn” is similar to that for “fulfill” and the word for “ivory” is similar to that for “deceive”. […]

Arthur T. Murray, translator of the original Loeb Classical Library edition of the Odyssey, commented: The play upon the words κέρας, “horn”, and κραίνω, “fulfill”, and upon ἐλέφας, “ivory”, and ἐλεφαίρομαι, “deceive”, cannot be preserved in English.

Again, we can see why cryptocrats would love this pun: It’s about deception & truth, and they pass deception for truth all the time! But there may be even another secret meaning: κραίνω krainu does not only mean “fulfillment”, it also means “ruling”! So “horn & ivory” may well be a pun about deceptive rulers, of which there are many others.

Even the gates may be a pun: The word πύλη pule for “gate” also means “gatekeeper” & “guardians”. The “gates of horn & ivory” could point to the spooks being “guardians of rulership & deception” or somesuch.

More research is needed for the Odyssey, but I hope you can see now how puns work, and that even for admitted puns, there may be secret spook meanings behind them that are not admitted. You can now try and browse the long list of spooky puns I think I found, and see whether you agree with me.